This guest post by Professor Calvin Jones, published on St David’s Day 2024, is part of Afallen’s ongoing work to stimulate debate about the opportunities to create prosperity in Wales by thinking and doing differently.

Header photo: the Amazon Warehouse (‘fulfillment centre’) in Swansea, obtained from Coflein.gov.uk.

“The original marginality, of course, was that of poverty, a cramped and pinched community of small commodity producers unable to generate capital … its most vivid symptoms the great droves of skinny cattle and skinny people tramping into England to be fattened.”

Gwyn Alf Williams

‘When was Wales?’

BBC Wales Annual Radio Lecture, 1979

When was Wales?

Gwyn Alf, love him, bless his cotton socks and his nailed-on Dowlais righteousness, wrote in 1979 about a Wales that was long-gone. A Wales whose hearts were manifold, Cymraeg and rural, and where Dowlais’ seventeen iron foundries would have seemed like… well Satanic mills. But he could have written something very like it about the 1870s, when our coal was rushed to the coast to power the Empire at sea; or the 1930s when we left in our hundreds of thousands to service the new light industries to London’s west. Or the 1990s, when Welsh-made VCRs and Camcorders and batteries and steel and car exhausts went out with other people’s names on them to be inserted into other peoples’ homes, or bolted onto other people’s stuff.

Or indeed, he could have written it about today.

There’s something very odd about this, at least on the surface. Basic economic theory tells us we can’t prosper without being competitive; without exporting; without paying our way in the world. Yet, for centuries, in varied ways, we’ve done just that. But without the ‘prospering’ bit. Dig a bit further, at the edges of economic theory (the bits that don’t get you audiences with PMs or lucrative speaking invitations in the City, trust me I know) and you realise that what you export matters. And exporting ‘basic’ commodities – y’know, the stuff that keeps us fed, watered, lit-up and warm – is a fool’s game. As is exporting people. Dig even further, so that your theoretical spade goes right through and you fall beneath notice, and you realise also that who owns stuff really matters.

You can’t understand Wales without understanding this. Ignore at your peril.

Ownership

A lack of ownership is endemic across Wales. It occurs in manufacturing; in utilities; in private services; and in real estate. It brings trouble. A lack of autonomy; of control over our economic – and hence social and environmental – future. The shaping of Wales by outside forces (and, let’s not forget, the shaping of the Gogledd and the west by those peskily numerous Hwntw) is limiting. It limits product diversification, and process (let alone product) innovation. It limits occupations, and hence wages, progression and inclusion. It limits prosperity, the business mix, clustering, and agglomeration – and hence market size and diversity, with consequent knock-ons to business formation, business retention and the scope and nature of inward investment. The characteristic of Wales as marginal – economically, politically, culturally – shapes it, shapes us, profoundly.

The impacts of our unequal relationship with the world are easy to see – and easiest to see in the economy. The oftenest quoted statistic is that of Gross Domestic Product, GDP, where Wales’ per-capita level was in 2021 quite staggeringly 25% below the UK average. Ynys Môn, along with a few other UK communities dominated by out-commuting is almost 50% lower. But turning to metrics that Governments really care about – tax revenues – makes the case even more starkly.

Wales’ tax revenues

As Figure 1 shows, Wales performs very poorly indeed on tax revenue streams that reflect the health and diversity of the economy. On a population share of 4.6% of the UK, we contribute some 2.8% of UK income tax – so on a per-capita basis, 40% lower (because hardly anyone in Wales earns much). Our per-capita corporation tax is 45% below the UK average (we’re stuffed full of tiny companies making no money). Our Capital Gains Tax – paid by both business and people for, well basically being capitalists – is an astonishing 67% lower on a per-capita basis (we own very little and what we do own never goes up). If this wasn’t bad enough, it turns out we pay pretty much our population share of VAT (meaning we pay 33% more VAT per unit of economic value added), and… more than our share of fuel duty as we traverse our wide-open spaces without an Elizabeth Line (or a bus route) to call our own.

Of course, the way out of this mess is economic growth. So it’s handy that the motor of innovation and growth, spending on Research & Development, is in Wales a healthy… [Checks notes. Checks notes again. Throws notes in bin.].

The de-industrialisation of Wales

None of this is at all new. The hustle and bustle of coal, and steel, and the consequent capital inflows, infrastructure and civic investments hid Wales’s fundamental economic marginality. Post World War Two, active regional policy and strong social safety net did much the same job. But even big numbers in attracting inward investment through the 1980s and 1990s could not mask the deep dysfunction uncovered by de-industrialisation, and the Thatcherite determination to throw Britain’s industrial regions out of the national economic tent, or continue the fiction that Wales was going places. There remained, however the narrative that taking this most globally-embedded of regions, and thrusting it even deeper into the global-competitive sharkpool (along with the similarly benighted North) would do the job of reconstruction and rebirth. Just a few more skills and entrepreneurs, some better start ups, and more roads and business parks to sate the hunger of ever-mobile firms and success would come…

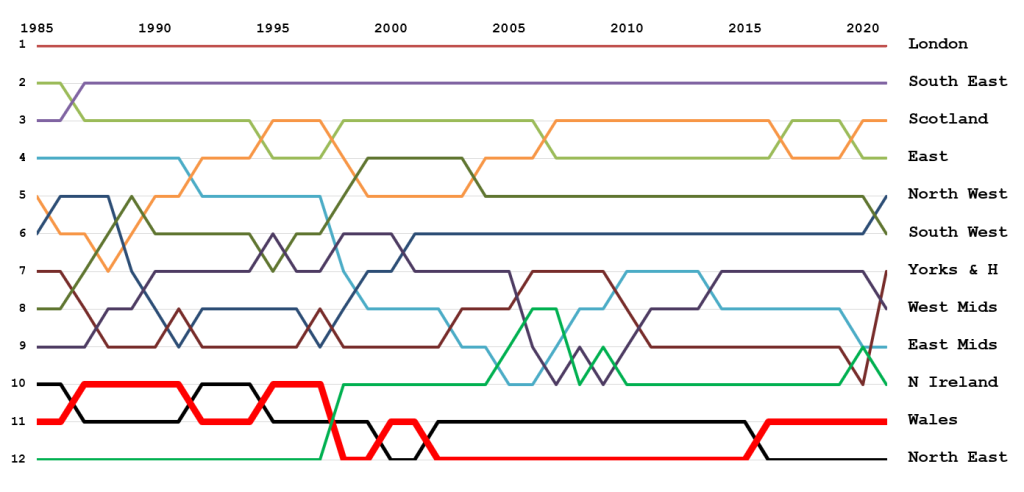

Instead, the picture has been one of ossification. If we rank UK regions by GDP per head, we see the same team, London, has won the ‘economic premiership’ in every one of the 37 years since comparable records began. The South East has finished second in all-but-one of those years, and the only change of note at the top has been canny Scotland, the wheel that squeaks, establishing itself as a fixture in the Champions’ League at the expense of the East Midlands. Meanwhile at the other end the regulation candidates are the same in 2021 as in 1985, and in only four of those 37 years has any of these perennial laggards dragged itself briefly out of the bottom three. And it wasn’t us.

In 1985, in the depths of Thatcherite hollowing out, and bloodied from the miners’ strike, Welsh GDP-per-head was at around 68% of London’s figure.

In 2021 it was 43%.

Go figure.

Figure 2: Ranking of UK Regions by GDP/GVA Per Capita 1985-2021

Blame the English?

It is tempting to blame this all on the noisy neighbours, the English. And it is 100% their fault. But whilst this was perhaps defensible a thousand years ago, since the Acts of Union in the 16th Century, the Welsh as individuals (if not Welsh as a culture) have been more-or-less equal to the English under the law. Welsh firms, workers, lawyers and accountants have been blessed with the full weight of the English Crown’s protection (but until 1993, only in Saesneg of course), and allowed full access to big English markets, and to key resources both in and beyond these islands (hallo the Empire!). Indeed, looking across Europe and beyond shows many culturally distinct minorities have, despite historic disapprobation of the majority, levered themselves into advantageous economic positions in their respective nation. The Basques and Catalans in Spain, and the Québécois provide an object lesson, Whereas Galicia, Italy’s Mezzogiorno and lots of First Nations an abject one.

Moreover, whatever historical happenstance and cumulative causality, today’s owners of Wales’ territorial capital are in many cases not English. In the energy sector for example we see key facilities owned by French and German multinationals, and equity ownership by European governments and municipalities alongside British entities. The economic dominance that draws Welsh graduates and companies away, and denies us infrastructure and capital is not England v Wales but London v the rest. Our history, geography, and geology placed us at the bottom of British heap. We are similarly at the bottom of the global value chain: still relatively rich in useful stuff, including energy and willing people, so worth resource-seeking inward investment when the valuable stuff, ideas or people can’t be bought out, shipped out or tempted away, but nowhere you’d go to sell anything! Too small. Too boring. Too poor.

Wales should be more Basque

But, but, but… our history is not our destiny. It is part of the reason for our poverty, but not the full story. Consider our Basque friends in Euskal Herria: Brutalised by Franco from the bombing of Gernika in 1937 until the day he died in 1975. Then living with decades of terrorism and unrest. An infrastructure deficit that leaves them still, in 2024, without a single high speed rail link in a Spain that seems to build them like Scalextric. A topography that never lets up, including a half-dozen peaks that would kick sand in the face of Y Wyddfa. But with a GDP per head only just behind that of the leader Madrid, and household disposable income some 30% higher than the Spanish average. Calvin, people say to me, what’s the lesson for Wales from the Basque experience? And I say… be chasing whales across the Atlantic in rowboats before Columbus was a boy. Cosy up to the Romans in their fights against those bloody Celts and cement your culture and language in the empire. Develop an approach to the economy that is embedded in your Cynefin and your people. Save, lend, borrow, own, locally. Care deeply about craft; building a reputation, European networks and prosperity on the consequent reputation. Be the closest bit of your country to big EU markets. Make actual products (cooperatively!) like bikes and buses. Have the confidence to believe in yourself; set your own rules, remember your past, keep your own coin, be self-reliant.

In short, be Basque.

The trouble is almost none of that is possible for Wales.

But… but… but… we don’t actually want to be Basque. Here’s what I think the problem is. The Basque Country has done incredibly well in carving a distinctive, almost unique position in the highly networked, financially integrated, trade-heavy, and fossil-fuelled European economy. But that economy is going away, to be replaced by something nobody can see yet but which will, despite all the chat about carbon capture and (permit me a small LOL) sustainable aviation, look completely different. It remains to be seen whether that small corner of Spain can lever past success in craft and process innovation, and its relative reverence for home and nation, into economic transformation. A landscape of highly specialised but relatively insular clusters, a ‘top down’ (and fairly inflexible) approach to innovation, and relative weakness in scientific and university research does not bode that well. Additionally, and importantly, their current success means the Basques have a lot to lose should current economic relationships and behaviours be upended. My own conversations over many years with colleagues from both favoured and less favoured bits of the Basque economy and innovation system suggests this is not an atmosphere that necessarilywelcomes robust ‘kicking of the conceptual tyres’ with open arms.

So back to Wales, back to the future, and onward to optimism; onward to a take where traditional economic weakness (and having relatively, nothing to lose) may turn into a modest advantage in upcoming battles. Where small green shoots of policy difference might grow into mighty oaks that shelter us from ever-growing storms. Where our own focus on home and hwyl, on cynefin and community, might find expression in a more robust, realistic, fair and responsible economy that bends to the wellbeing of people, here and elsewhere. But if this is to happen, it won’t happen by accident. And it won’t happen without tough and honest choices, and the slaughter of some very sacred cows. Without radical policies, coherent across time, place, and topic. Without clear eyes on our destination and what’s needed to get there. And without some practical, clear and thoughtful policies. Done now and with feeling.

And that, dear reader, is where we will be going next.